What to Know

- Bidding to address a mental health crisis on New York City streets and subways, Mayor Eric Adams announced Tuesday that authorities would more aggressively intervene to get people into treatment, describing “a moral obligation” to act, even if it means involuntarily hospitalizing some.

- The mayor’s directive marks the latest attempt to ease a crisis decades in the making.

- It would give outreach workers, city hospitals and first responders, including police, the discretion to involuntarily hospitalize anyone they deem a danger to themselves or unable to care for themselves.

Bidding to address a mental health crisis on New York City streets and subways, Mayor Eric Adams announced Tuesday that authorities would more aggressively intervene to get people into treatment, describing “a moral obligation” to act, even if it means involuntarily hospitalizing some.

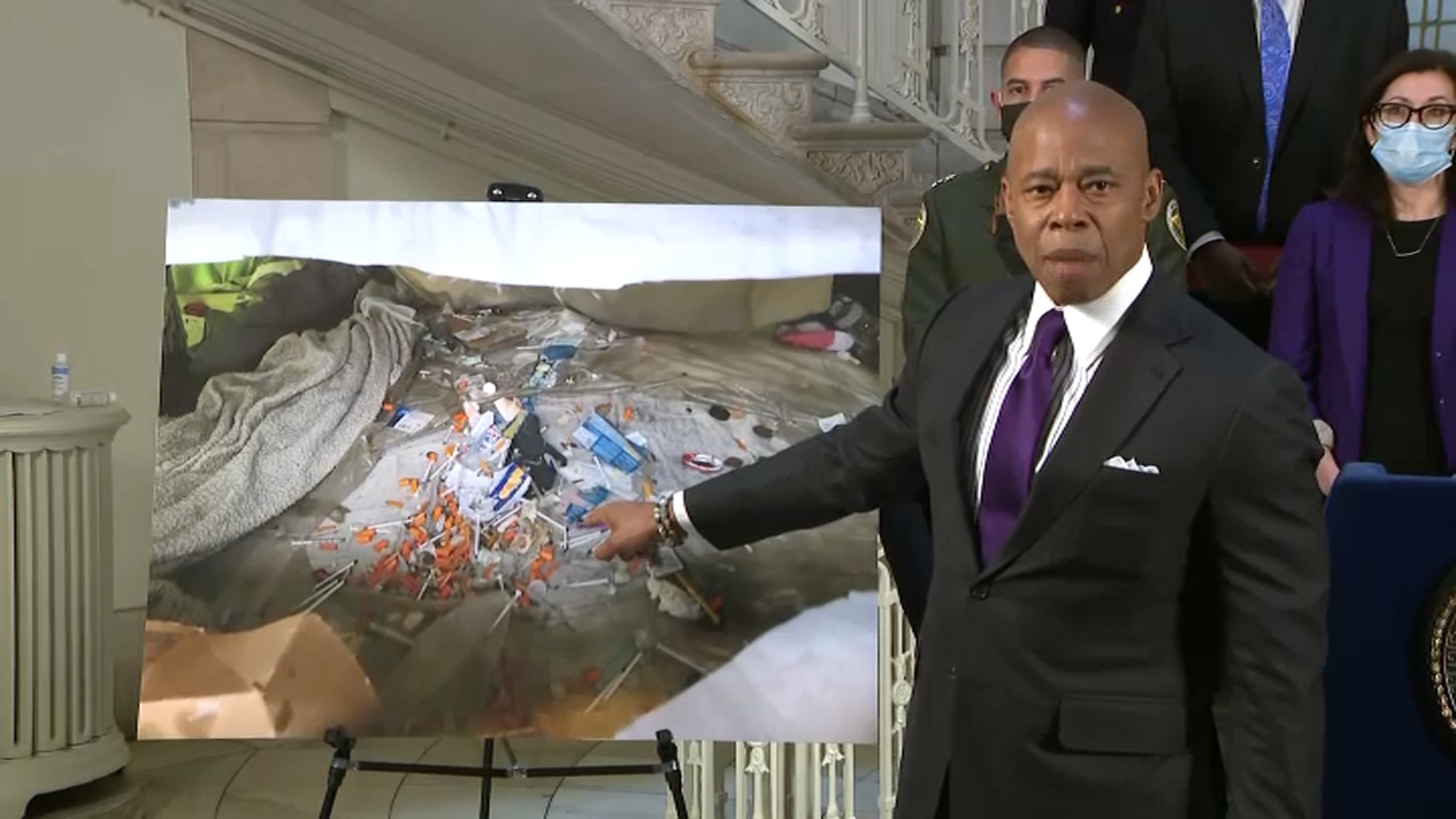

“These New Yorkers and hundreds of others like them are in urgent need of treatment, yet often refuse it when offered,” Adams said at a news conference, noting that the pervasive problem of mental illness has long been out in the open.

“No more walking by or looking away,” the mayor said. "You are not watching people talking to themselves, shadowboxing, unkempt — we are pretending as though we don’t see."

Get Tri-state area news and weather forecasts to your inbox. Sign up for NBC New York newsletters.

The mayor’s directive marks the latest attempt to ease a crisis decades in the making. It would give outreach workers, city hospitals and first responders, including police, the discretion to involuntarily hospitalize anyone they deem a danger to themselves or unable to care for themselves.

“The very nature of their illnesses keeps them from realizing they need intervention and support. Without that intervention, they remain lost and isolated from society, tormented by delusions and disordered thinking. They cycle in and out of hospitals and jails.”

State law generally limits the ability of authorities to force someone into treatment unless they are a danger to themselves, but Adams said it was a “myth” that the law required a person to be behaving in an “outrageously dangerous” or suicidal way before a police officer or medical worker could take action.

As part of its initiative, the city is developing a phone line that would allow police officers to consult with clinicians. The person in charge of the city’s 11 public hospitals said if there’s no time to make a proper assessment, let the emergency room do it.

"Somebody looks or acts psychotically, you’re not gonna know if it’s fentanyl or mental illness," said NYC Health and Hospitals CEO Mitchell Katz.

The mayor’s announcement was met with caution by civil rights groups and advocates for the homeless. Homeless policy experts say the new strategy fails to account for a lack of services, even for those who do want help, while overstating the risk of those who don’t.

"Mayor Adams is really feeding into a harmful narrative that people dealing with mental health challenges and are without housing are dangerous," said Jacqueline Simone of the Coalition for the Homeless.

A coalition of community groups, including the Legal Aid Society and several community-based defender services, said the mayor was correct in noting “decades of dysfunction” in mental health care. They argued state lawmakers “must no longer ‘punt’” to address the crisis and approve legislation that would offer treatment, not jail, for people with mental health issues.

“We are heartened to hear that Mayor Adams acknowledges that community-based treatment and least-restrictive services must guide the path to rehabilitation and recovery,” the groups said.

Other key questions remain, such as where the city will find other beds. The state has pledged 50, but hundreds of other beds the city operates inside hospitals have been closed in the pandemic.

The mayor said he has begun deploying teams of clinicians and police officers to patrol the city’s busiest subway stations.

In addition, the city is rolling out training to police officers and other first responders to help them provide “compassionate care” in situations that could cause the involuntary removal of a person showing signs of mental illness in public places. First responders who encounter someone who might be a risk to themselves or others must either "transport the individual to the closest appropriate hospital" and "remain with (the) patient until they have been registered by the hospital as a patient."

“It is not acceptable for us to see someone who clearly needs help and walk past,” Adams said in announcing the program. “We can no longer deny the reality that untreated psychosis can be a cruel and all-consuming condition that often requires involuntary intervention, supervised medical treatment, and long-term care. We will change the culture from the top down and take every action to get care to those who need it.”