The owner of a carriage horse that collapsed on a midtown Manhattan street, seen on startling video, faced charges at a Department of Health administrative hearing on Friday.

Ryder went down on 9th Avenue last month with his owner, Colm McKeever, at the reins. According to health department documents, Ryder's owner falsified birth records and tried to pass the horse off as 13 years old. A veterinarian who checked out the horse after its fall determined Ryder to be around 26 years old, too old to be licensed as a carriage horse in New York City.

The city's investigation claims McKeever "made false and misleading statement, or presented forged documents" in April when during the horse's initial examination, subtracting 10 years from Ryder's date of birth. Attorney information for McKeever was not known.

Since the horse's shocking collapse that renewed calls for a ban of horse-drawn carriages in the city, Ryder has been retired to a private farm upstate. The horse has also been receiving treatment for a neurological parasite, the union that represents horse carriage drivers said.

Get Tri-state area news and weather forecasts to your inbox. Sign up for NBC New York newsletters.

The union outlined new safety protocols following Ryder's fall to more closely watch the conditions of working carriage horses boarded at the city's stables. Those measures include biweekly medical checks of the horses' heart conditions and formation of a committee to catch and intervene on matters of health and safety early.

The union said that a veterinarian issued Ryder a preliminary diagnosis of EPM, or Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis — an infection caused by possum droppings.

"The neurological effects of the EPM caused the horse to stumble and fall as the carriage driver is trying to change lanes and turn here on 45th street on the way home," said Christina Hansen, a spokesperson for the carriage drivers' union. "And once he was down, he had difficulty getting up again from the neurological symptoms of EPM."

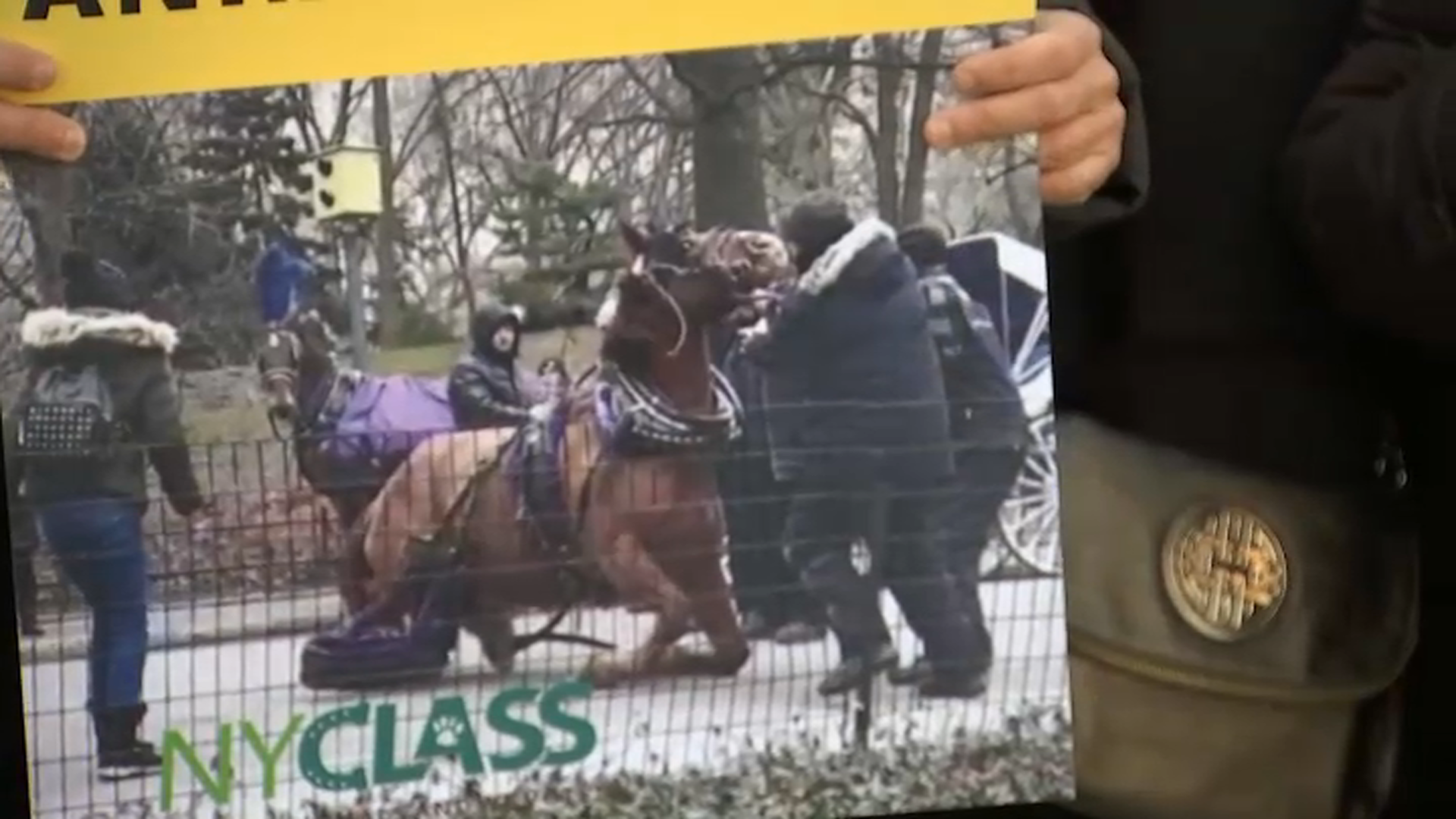

Hansen said that the video of Ryder on the ground is being weaponized by activist groups, and that he was in "rough shape" when he came into their program after being used as a buggy horse for a Pennsylvania farmer. She also said that the horse was not overheated or dehydrated.

Video difficult to watch captured Ryder's collapse Aug. 10 when he fell suddenly while pulling the cart up Ninth Avenue. A witness said that after the horse went down, the man driving the carriage started to hit the animal with a small whip, hoping to get it back on its feet.

The driver had no choice but to let the horse lay there, while the NYPD doused it with water and ice, assuming it had suffered from heat exhaustion. Ryder stayed resting on the hot pavement for some time, but eventually got back up on its own.

Whether Ryder collapsed as a result of EPM or if was heat-related doesn't matter much to critics, however. The incident has reinvigorated their calls to end horse-drawn carriages in the city for good.

"They don’t belong in the city! It has to stop," said Rachel Ejsmont, an animal rights activist. "We’re fed up, it's traumatizing for us."

There are 200 licensed carriage horses in NYC, an industry that includes 130 active drivers. The industry could face a seismic shift, all thanks to a bill by Queens City Councilmember Robert Holden that would force carriage drivers to switch to electric carriages — a move that can cost anywhere from $20,000 to $30,000.

"Where they have the electric carriages now, the drivers love it because they work in the heat, they can work in the cold," Holden said. "This is 2022, not 1822. We need to look at how we treat our animals, and we’re not doing a good job."

But the drivers, and their union, disagree. Hansen worries that no horses will mean less business from tourists, and wonders who is going to pay for the new electric carriages.

"I’m a horse person through and through. I’m not a golf cart driver ... There’s no evidence that they’ll make enough money to support their families with it," she said. "(Ryder) would have been disposed in the slaughterhouse, except that he became a carriage horse."

Then there's the question of where the out-of-work horses would then go, and how would their veterinarian bills get paid. But People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and political action group NYCLASS said that wouldn't be an issue.

"We can make sure that a home is available to every single horse being used by this industry," said Ashly Byrne, a member of the group. "We have safe loving homes that they can be retired to so again there’s no excuse."