The students of Mike Bigelow's first-grade class light up when they're asked what they've learned about Asian American history and social studies this year.

Ayansh Grover, 7, says he observes Hindu culture and shared with his classmates how he celebrates holidays like Diwali and Holi.

Every Tuesday, the class practices saying "hello" in a language represented by a classmate and learns more about the country where that language is spoken. Lila Cortese, 6, shares how they greeted one another by saying "annyeonghaseyo," or "hello" in Korean, that morning.

The Skinner North Elementary students in Chicago are some of the first to go through school in an era where lessons about Asian American history are a staple of their lesson plans.

Get Tri-state area news and weather forecasts to your inbox. Sign up for NBC New York newsletters.

Through the Teaching Equitable Asian American Community History, or TEAACH, Act, Illinois public K-12 schools must include a unit on the history of Asian Americans in Illinois and the Midwest, as well as Asian Americans' contributions toward advancing civil rights in the U.S. Illinois became the first state to pass such a law mandating these requirements in 2021.

Since then, similar laws have passed in New Jersey, Connecticut and Rhode Island — and the movement is growing with support from students, teachers, parents and education advocates around the country.

'They see themselves in these stories'

Money Report

Smita Garg, 42, previously taught elementary school and is a mom of two children, ages 11 and 6, in the Chicago Public Schools system. She remembers growing up Indian American in a predominantly white suburb of Cleveland, Ohio, and over time learning to celebrate and share her own multicultural heritage with others.

She didn't know much about Asian American history even as she learned to be an educator: "Having grown up in public education in the Midwest and then learning to be a teacher in a master's program and not having any of this background — it was jarring." Garg says that by grad school, she began researching more about Asian American labor movements, immigration patterns, civic engagement and activism.

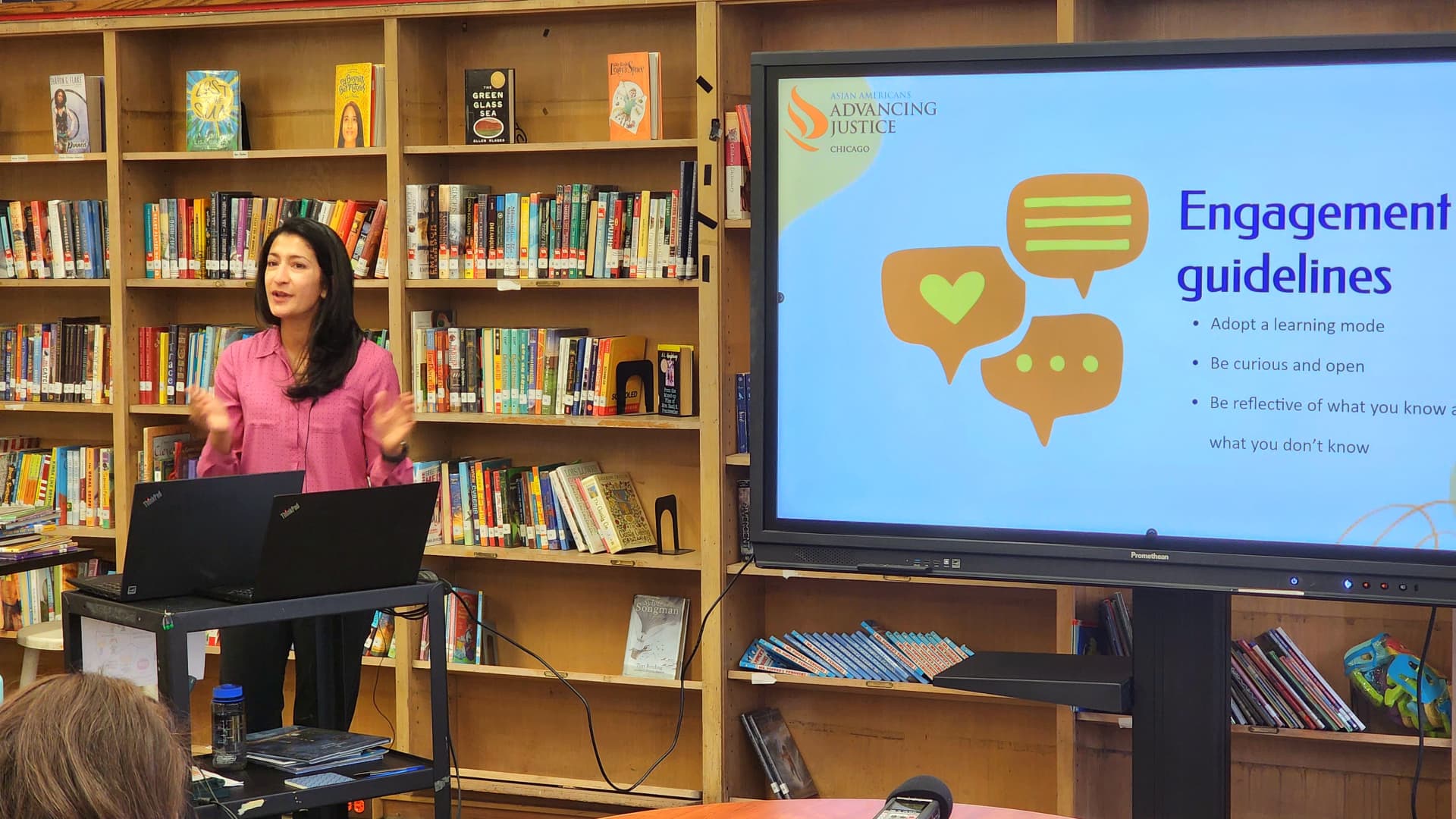

When the TEAACH Act passed in 2021, she joined Chicago's chapter of the Asian Americans Advancing Justice, or AAAJ, as a volunteer to pull together curricular resources for K-12 Asian American history lessons.

The resources share ways teachers can incorporate Asian American history and cultural studies into the Illinois School Board of Education's existing learning standards.

For example, a kindergarten teacher planning a lesson about U.S. holidays may include holidays of diverse groups and the historical figures who make those days special, while a fourth grade democracy unit could include a lesson on Larry Itliong, the Filipino American labor organizer and one of the founders of the United Farm Workers union.

And starting with the 2022-23 school year, Illinois history teachers must include lessons about the wrongful incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, as well as the service of two Japanese American combat units, the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Infantry Regiment.

Garg says it's important for AAPI students to see themselves reflected in textbooks as critical to the development of the U.S, and for their non-AAPI peers to recognize that as well. "History and how you connect to it — or not — offers us a sense of identity. And so without that connection, it's not quite the same then how you view your place in this country and perhaps how others see you in it."

As a parent seeing her Asian American children now learning this curriculum, "I love it," she says. "They see role models, and I think that's really important. They see themselves in these stories."

Advocates say teaching AAPI history is key to reducing anti-Asian discrimination and violence

Organizers with the AAAJ Chicago drafted the bill language for the TEAACH Act in February 2020, but the Covid-19 pandemic stalled advocacy efforts. At the same time, the need for Asian American history standards were urgently clear: Individuals reported nearly 11,500 incidents of anti-Asian hate between March 2020 and March 2022, according to data from Stop AAPI Hate, a coalition formed to address the pandemic-era spike in racialized violence against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

"We saw Asian American history education as one critical part of combating the rise in anti-Asian racism, and sentiment," says Grace Pai, executive director of AAAJ Chicago. "Without understanding why Asian Americans have been blamed and scapegoated for things like the pandemic, it's hard to stop that behavior from escalating into incidents of harassment or violence."

Advocates say the exclusion of Asian Americans at many levels, from classroom lessons to governing bodies to movies and TV screens, renders many AAPIs invisible to the general public. Three in 10 Americans can't identify a significant Asian American historical event or policy, according to a 2023 survey of 5,235 people by The Asian American Foundation, or TAAF.

When asked what they know about AAPI history, the No. 1 response is about Japanese incarceration during WWII, "and only about 14% of Americans across the country are even familiar with Japanese incarceration," says Norman Chen, CEO of TAAF. "It's such a historic and painful moment in our country's history, so it's really necessary that we have more of AAPI history taught in schools to learn from the past and make sure we don't repeat the mistakes that occurred."

Progress and pushback

More work is being done to push for AAPI history requirements in public schools: One organization, Make Us Visible, has efforts in over a dozen states. A majority of Americans, 3 in 5, think incorporating the Asian American experience into the teaching of U.S. history is important, according to the TAAF survey.

In states where these initiatives now exist, "we've seen students and parents share with us stories about, how for the first time in their lives when they open a textbook, they're starting to be able to learn more about our community," Chen says. "It's very powerful."

But progress to teach inclusive American history, including of marginalized groups, isn't happening evenly. During the 2020-21 school year, nearly 900 school districts across the U.S., representing 35% of all K-12 students, were affected by local district efforts to restrict so-called "critical race theory," or lessons that discuss issues of race or racism, according to research from UCLA and UC San Diego.

Parents, educators and advocates are "deeply concerned" about efforts to restrict inclusive history curriculum, says Pai of AAAJ Chicago. "History is history. It shouldn't be disputed what happened or what the facts are that we should be sharing with students, but unfortunately it's become highly politicized. It is really a disservice to our young people when we are not telling the whole truth."

'This is a stated need'

Once the Illinois bill was signed into law in July 2021, AAAJ Chicago developed a professional workshop and has trained over 1,300 teachers from across the state how to teach Asian American history.

The teacher trainings are invaluable to Bigelow, 36, the first-grade teacher at Skinner North. He has been a teacher for 12 years and noticed that, after a stint in Michigan and returning to Chicago, the demographic makeup of his classroom shifted over the years, and "finding resources and books that match their identities was really difficult."

Bigelow says he was was excited to see teacher training to incorporate AAPI social studies into his classroom and approaches the learning curve with "humility and a sense that my awareness of Asian American history is limited."

He learns from his students as they learn from him. His students Valentina Zhu and Helena Zhang, both 7, gave him practice cards to learn Chinese phrases at the beginning of the year, and Rachel Tsang, 7, encouraged him to try Duolingo, the language-learning app.

The new cultural guidelines encourage classmates to build relationships and learn from each other. "A lot of educational theory is based on how most learning is social, and you have to have relationships to learn,' Bigelow says. "If you don't know who people are, you can't learn very well from them."

Pai adds that it's important that lessons about AAPI history and culture are embedded into overall themes within classroom curriculum. "Often Asian American history is only talked about in the context of social sciences, but you can also incorporate Asian American history into English language arts, math, or into physical sciences," she says.

"The great thing about the TEAACH Act is that it opens the door and says, 'This is a stated need. This is something that we have to do,'" Bigelow adds. "And it provided [a resource] for me as an educator who wants to learn and do more."

Want to be smarter and more successful with your money, work & life? Sign up for our new newsletter!

Get CNBC's free report, 11 Ways to Tell if We're in a Recession, where Kelly Evans reviews the top indicators that a recession is coming or has already begun.