- A majority of American workers support more unionization inside their own companies, according to the CNBC|Momentive Workforce Survey.

- Worker rights are not a partisan issue, with almost half of Republicans voicing support for unions.

- Actual union membership remains low and election wins scarce, and it will take sustained public, worker and investor pressure to cement structural changes in the relationship between labor and management.

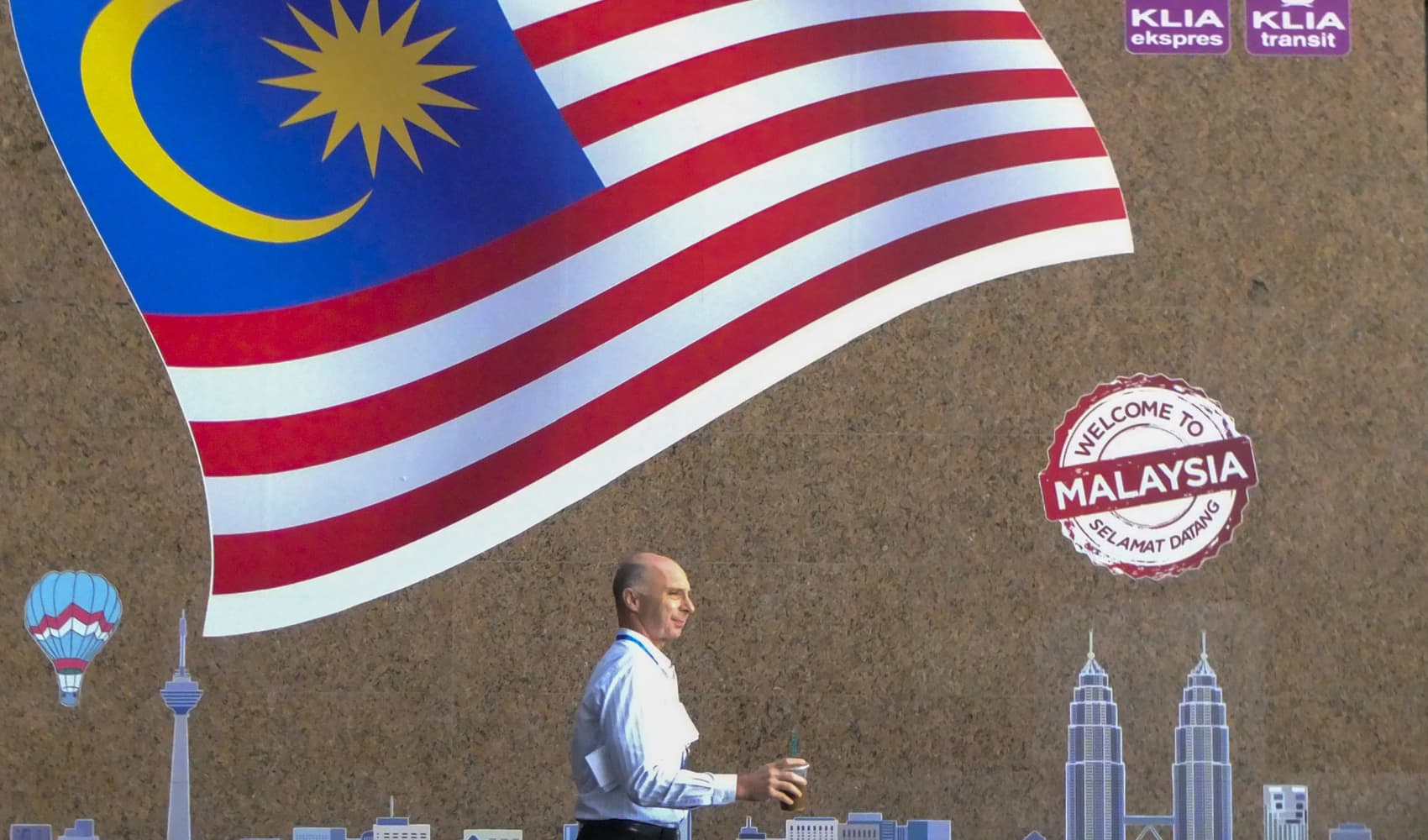

From Starbucks to Amazon to Apple, the recent headlines show that the biggest companies in the world can't duck the union issue. But the issue isn't isolated to a few iconic companies operating in retail. While union membership remains at a multi-decade low, a CNBC survey finds that a majority (59%) of workers across the U.S. and across all sectors say they support increased unionization in their own workplaces.

The recent CNBC|Momentive Workforce Survey reinforces recent findings from Pew Research Center and Gallup polls, which both show widespread support for labor unions among the public. And it does not break down into a clearly partisan political issue. While Democrats are about twice as likely as Republicans to have a positive view on unions, the CNBC survey finds bipartisan support, with 46% of Republicans in favor of increased unionization at their work.

"This really isn't the partisan issue that many assume," said Laura Wronski, senior manager of research science at Momentive, which conducted the survey for CNBC in May among more than 9,000 workers across the country.

Get Tri-state area news and weather forecasts to your inbox. Sign up for NBC New York newsletters.

What is taking place in the current labor market is unlike anything since the late 1970s, according to MIT Sloan School of Management professor Thomas Kochan, who has been studying unionization and conducting his own surveys on the issue. For several decades starting in the late 1970s, only one-third of workers nationally said they would vote "yes" to a union. But in 2017, that number jumped to 48%. "That was the first indication of a big change and all the evidence since has reinforced that," Kochan said.

The pent-up demand for more representation was reinforced by the pandemic, during which conditions for front-line workers received public scrutiny, and further intensified by a tight labor market. While it is just a small number of union drives so far, Kochan says the number of worker groups asking voluntarily for representation and elections has increased at a rate that has to be taken seriously. "Workers are now taking more direct action," he said.

Workers are emboldened in a job market that offers two open positions for each worker, but whether this will lead to a fundamental restructuring of labor-management relations remains unclear. The relatively small successes at a limited number of Starbucks cafes are not an indication of the snowballing that would need to occur to turn worker support for unions into greater action across the economy. And labor experts point out that while the recent Amazon union win in New York City was a big one, the biggest union drives in recent years, whether at VW or Boeing, were notable failures.

Money Report

"I'm of the school that says there is something happening, but no indication yet it is even going to amount to a sizable increase in the level of unionization," said Harry Katz, a professor and expert on collective bargaining at Cornell's School of Industrial & Labor Relations. "6,000 Amazon workers is important ... cafes, my heart is with them, but 15 to 20 per store, even though it's now 50 stores, doesn't amount to a lot. I'm not so sure the tide has turned so substantially yet," he said.

The CNBC survey results show that there is nuance within the majority support for increased unionization. When asked if unions have too much, too little, or just the right amount of power, survey respondents were evenly divided among all three responses.

This view matches what labor experts say is a push and pull among workers between wanting a stronger voice on the job but being wary of conceding that voice to traditional labor leaders. The majority of workers, they say, prefer cooperative engagement to an adversarial relationship.

"There is still some ambiguity in the minds of workers about turning to unions as the institution that will provide the answers," Kochan said. "They are wary of having another boss. They already have one and don't want to be told by largely older union leaders 'this is the way we do it.'"

However, once workers start organizing, getting support from unions can be helpful, and for a new generation of workers — many young workers who are college educated but also underemployed —these connections are likely to stay with them throughout careers at multiple companies.

What is taking place within the workforce will require a shift in managerial ideology from what has long been an ingrained knee-jerk reaction to resist any forms of representation.

"They are leaders and good people and care about their workforce, and to them, 'The union will just get in the way.' We've got to address that issue and engage the business community in recognizing these pressures are not going to go away," Kochan said.

The worker calls for more representation are playing out at levels below formal union elections, and are not limited to core employee demands related to wages, hours and working conditions. They want a say on issues as diverse as use of AI systems, company mission, and structural changes within the workplace, for example, worker councils which engage with management directly on issues like dispute resolution, or even a worker representative on the board of directors.

For the C-suite, it is a big leap.

"They prefer to operate with direct communication and that goes back to strong notions within American management about their right to manage, and private property rights, and the law has supported that," Katz says.

Starbucks hasn't substantially changed its tune, nor has Amazon, and Apple last week stayed within the legal bounds of warning workers about the negative repercussions of joining a union.

The legal environment remains favorable to companies, as does the fact that the longer it takes for a union drive to play out, the more likely it is for momentum to wane.

"In the midst of campaigns where companies are able to talk to workers very aggressively, and sometimes more moderately, about the 'cost' of unionization and risks that follow, worker support often wanes," Katz said. "In some campaigns, employers cross the line and are coercive, but even in cases where they are not coercive, we see a long history that worker support wanes as campaigns go on," he said.

The history of labor movements also shows that it operates with its own cyclicality, and in tighter labor markets in which workers face less risk about losing jobs, there is a greater union push. But that can only go so far. The latest private payrolls report showed the slowest growth for new jobs in the current economic recovery, but by the government data, companies remain in a war to hire, if off the peak during the recent period of employment gains.

"What really matters is structural change," Katz said.

This type of change happened shortly before, and then through the World War II period, and into the early 1950s, and couldn't be explained by the business cycle effect of a tighter labor market.

"The reason unionization has declined over the past four decades is not that workers don't want it, it's that policy relentlessly reversed," said Heidi Shierholz, a former chief economist for the Department of Labor and current president of the Economic Policy Institute, which advocates for low- and middle-income workers.

Union membership stood at 14 million workers in 2021, representing roughly 10 percent of American workers, a decline from 20% in 1983.

While President Biden is using the "union" word more than the two most recent Democratic Party presidents before him, and the National Labor Relations Board issued a memo last month taking aim at tactics used by Amazon and Starbucks, saying the law was ripe for an update, this level of change won't happen unless there is a sustained period of public engagement with the issue.

C-suites are more sensitive to what customers think, and they will worry about the polling data showing more sympathy for unions, and be more hesitant to be perceived as anti-union, labor experts say. But investors and customers will need to apply more pressure for momentum to translate into new legislation. Law will change, they say, only as a byproduct, or secondary condition, of sustained public support.

"The big question I get asked is will this be a turning point, or just a flash in pan, and I think the answer is it depends on how these events are dealt with," Kochan said.

He is advising C-suites to accept that the labor relations playbook of the past 50 years may be ending, and leading with the message that instead of putting all of their resources into union avoidance, management should invest in a more positive relationship. But he has no illusions about the degree of difficulty involved.

"I am a veteran of lots of backroom labor versus business efforts to change policy, and it all failed in the late 70s, and during Clinton and Obama administrations, because the public never really engaged with the issue, and right now, we have a situation where the public is recognizing it, and that's big," Kochan said.