Last summer Pariesh Steele, a New York City correction officer assigned to the Anna M. Kross jail on Rikers Island mysteriously stopped coming to work.

Department of Correction investigators placed phone calls to his Brooklyn home. He didn’t answer. Steele’s attendance record at Rikers was already less than stellar. In 2018 and 2019 he had been labeled “chronic absent” after calling out sick 103 days in a single year. But in the summer of 2021, DOC records show he didn’t even call to tell anyone he was feeling ill. He just stopped showing up for his shifts. After he missed about four months’ of work - without providing any explanation - Sarena Townsend, the former top DOC internal affairs investigator, signed off on disciplinary charges.

Steele was deemed Absent Without Leave - AWOL.

Get Tri-state area news and weather forecasts to your inbox. Sign up for NBC New York newsletters.

“It’s an embarrassment,” Townsend said in an interview with the I-Team. “This is a culture of game-playing. It has been happening but only now that the staffing crisis has exploded to what it was has it become more publicized.”

Pariesh Steele is one of 25 correction officers facing the most egregious departmental charges for skipping work in the last two years. The News 4 I-Team used New York’s public records law to uncover documents outlining the allegations against him and two dozen more of the city’s no-show C.O.’s.

The magnitude of their collective absenteeism is breathtaking.

One jail officer stands accused of being AWOL for 170 shifts in nine months between September of 2020 and June of 2021. When he did show up to work, records indicate he routinely arrived two hours late.

Another correction officer is accused of using 197 sick days in a single year. A staff member assigned to one of the infirmaries on Rikers Island is accused of calling in sick 325 days in just over 2 and a half years. When an investigator visited her home, she wasn’t there.

New York city’s correction officers, along with other uniformed public safety workers, have the right to nearly unlimited sick days because their jobs carry unique physical dangers. But Townsend said she believes hundreds of jail staff members began abusing that policy during the pandemic.

“We saw people who were out for months and months who were continuing to get paid by the department and not coming to work,” Townsend said.

Last summer the de Blasio Administration began sounding frequent public alarms about dangerously low work attendance at Rikers Island. At one point, 1 out of every 5 jail employees called out sick or was AWOL.

So where was Steele during the four months he skipped work last summer?

According to police records and court documents, he spent part of the time away from work getting arrested in Pennsylvania. A criminal complaint filed outside Lancaster says Steele was caught at a FedEx store trying to mail 3 pounds of marijuana to Puerto Rico in June. When investigators examined Steele’s credit card records, they found he’d also spent nearly $3,000 on Puerto Rico hotels — during the same timeframe he was marked absent from his job at Rikers Island.

Steele’s criminal attorney did not return the I-Team’s request for comment, but a spokesman for prosecutors in Lancaster said he believed the correction officer intends to plead not guilty to the drug charge.

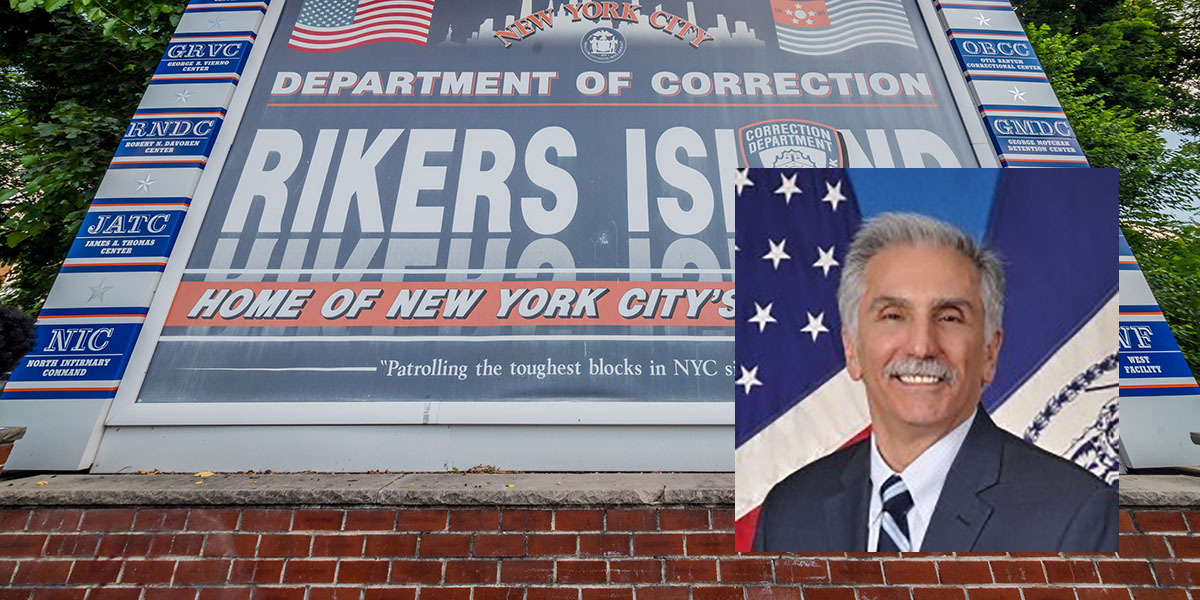

Last month, Townsend says she was fired from her job as the top internal affairs official at Rikers Island after she said the newly appointed DOC Commissioner, Louis Molina, suggested she should downgrade or get rid of two thousand disciplinary cases against uniformed jail officers.

She said no.

“I was fired because the unions did not like that I was holding their members accountable and the Commissioner wanted to be in good favor with the unions,” she said.

Molina declined an interview request from the I-Team, but he recently characterized the dismissal of Townsend as a routine personnel decision having nothing to do with efforts to reduce penalties for no-show jail staff.

“In my six weeks at this department, I have witnessed an appalling number of deficiencies that began under the previous administration. This is exactly why I made changes in our leadership,” Molina wrote in a statement to the I-Team. “I am committed to addressing these systemic failures to ensure that we take appropriate disciplinary actions in cases where staff are AWOL or abusing our leave policies.”

The DOC says about half of the chronically absent jail officers named in the documents obtained by the I-Team have already resigned or have been successfully fired. Another half still have their jobs as they await administrative hearings that will determine if they can keep their jobs.

The Correction Officers’ Benevolent Association, which represents much of the city’s uniformed jail staff denies explicitly requesting Townsend’s removal, but has long criticized her disciplinary practices as heavy handed.

“She was overzealous with discipline,” said Benny Boscio, the COBA President. “Not every discipline case should result in a 30 day or 60 day suspension.”

Boscio defended the nearly unlimited sick days correction officers are allowed to use, citing an alarming spike in assaults on uniformed jail staff. According to the 2021 Mayor’s Management Report, prisoner attacks on correction officers have jumped 130 percent in the last five years. Stabbings and slashings in city jails are up by 50 percent. The union has argued the staffing crisis isn’t a product of malingering employees, but rather the failure to hire hundreds of new correction officers to backfill the ranks as legitimate injuries become more common.

“I go visit officers in the hospital for broken noses, eye sockets, torn shoulders,” Boscio said. “It is a staffing crisis based on them not hiring in 3 years. Because the de Blasio Administration decided they wanted to close Rikers Island and they said let’s just let Rikers Island rot.”

It is true, the number of city correction officers has declined to about 7,200, a 25 percent drop from five years before. But in that same period, the prisoner population at city jails has plunged 40 percent — from around 9,100 to less than 5,500.

Most of the decrease can be traced to bail reform. Last summer, the federal monitor overseeing Rikers Island noted the dramatic drop in people housed in Rikers has left the Department of Correction “with one of the richest staffing ratios in the country.”

“We are pretty well staffed,” said Vinny Schiraldi, the former Correction Commissioner who was let go when Mayor Eric Adams took office.

Schiraldi said he fears the new administration is seeking to dismiss or downgrade disciplinary charges against AWOL jail officers. A move that would betray the thousands of correction officers who reliably show up.

“When I went through those facilities and talked to them? They were glad I was disciplining people for AWOL-ing. They were glad I was going and knocking on people’s doors to get sick people to come back in because they were the ones working triples. They were ones in understaffed facilities,” Schiraldi said. “They deserve their colleagues to come to work and do their damn jobs.”

After just a few weeks on the job, Commissioner Molina says he has been able to induce significant numbers of correction officers to do just that.

“More than 1,100 uniformed staff members have already returned to work since my appointment,” Molina wrote.

Townsend, who recently signed on as a partner at the law firm Townsend, Mottola & Uris, said the announcement strains credibility.

“How do you say that 1,000 officers who were genuinely out sick this entire time miraculously recovered after the removal of the disciplinarian? It’s an admission of guilt.”