South African-born playwright Athol Fugard returns to Signature Center, his longtime New York home, to direct an elegant revival of his autobiographical and still-resonant Apartheid-era drama “Master Harold … and the Boys.”

Set in 1950, in a Port Elizabeth tea shop, “Master Harold …” was the first of Fugard’s plays to premiere outside his native country, where it was initially banned. The story depicts the friendship between two black men, who work at the shop, and a young white boy, whose parents employ them.

On a grander scale, the story is about institutionalized racism.

“Master Harold” originally landed on Broadway in 1982, with Danny Glover as impetuous busboy Willie. Glover graduated to the role of paternal stand-in and headwaiter Sam in a revival two decades later.

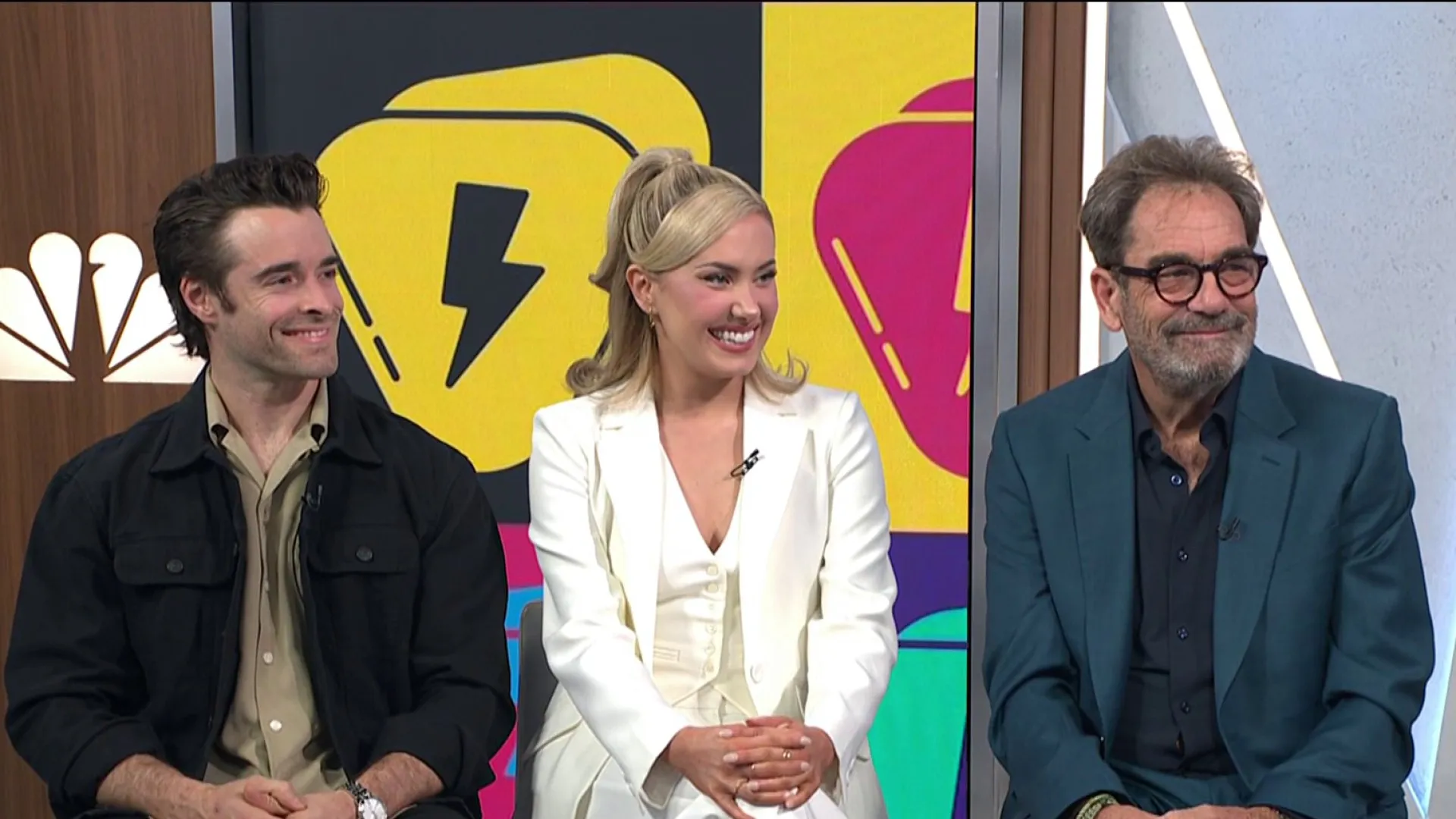

This time, the three stars are Leon Addison Brown (“Misery”) as Sam; Sahr Ngaujah (“Fela!”) as Willie; and Noah Robbins (“Brighton Beach Memoirs”), as the title character, the coming-of-age white teen who has been brought up around the older men and has yet to cement his own notions of race and class division … though he’s coming closer.

Hally’s real father, a drunk, is in the hospital, and though Hally won’t admit it, the good medical care isn’t the main reason he hopes the old man will stay there. The rainy afternoon’s events are set in motion when Hally’s mom calls. Sam thinks she’s bringing Hally’s father home from the hospital.

Throughout “Master Harold …,” Hally will misdirect his anger at his father onto the two men who’ve tended to his emotional needs in ways the boy can’t even always recall. Fugard’s drama is slow to unreel, but builds to a confrontation audiences will find absorbing, no matter that Apartheid ended a decade after the play’s debut.

Broadway

Brown is compassionate and believable as the pensive, centered Sam, who in a famous anecdote about kite flying manages to characterize both the largest issues of the era and the uniquely personal relationship he has with his de facto charge.

Ngaujah, as the more mercurial Willie, has nice chemistry with counterpart, particularly when the talk turns to ballroom dancing, Willie’s escapist hobby.

In Robbins’ interpretation, Hally is never very likable, coming off as a young Napoleon from the start. Because his Hally is such a brat, the play is denied a larger sense of any escalating ferocity within the boy. That said, I appreciated the way the actor depicted his shock at the racist words coming from his own mouth after he verbally targets Sam.

There’s some hopeful irony in listening to Hally and Sam talk figuratively about a social revolutionary who might change the country. For audience members who have followed developments in South Africa, “Master Harold” is a snapshot of how social progressives were thinking, before they could ever imagine a day when Apartheid would end.

“Master Harold … and the Boys,” through Dec. 4 at The Pershing Square Signature Center, 480 W. 42nd St. Tickets: $35 and up. Call 212-244-7529.

Follow Robert Kahn on Twitter@RobertKahn